There are design nerds, and then there are design nerds whose handling of the subjects they’re passionate about manages to transform abiding obsessions into illuminating, resonant art. Such is the touch brought by the graphic designers-turned-publishers Jesse Reed and Hamish Smyth to the first group of books that their small, Brooklyn-based publishing company, Standards Manual, has produced in just the past few years.

The press’s newest title, New York City Transit Authority: Objects, vividly exemplifies Reed and Smyth’s finely tuned approach, but in order to understand how and why it does, it helps to know a bit about how they somewhat unexpectedly became publishers, a story that often seems to be the stuff of happenstance and uncannily good timing.

Reed, who was born in Australia to American parents and returned to the United States as an infant, where he grew up in Ohio, told me during a recent interview, “My undergraduate thesis project at the University of Cincinnati was the redesign of New York City’s subway map.” He asked as much as he stated, “Maybe, somehow, a lot of what we’ve done can be traced back to that project?”

After graduating from his university’s School of Design, Architecture, Art and Planning (DAAP), he landed a job in New York at the Museum of Modern Art’s in-house design department and in 2012 joined the staff of Pentagram, the international design consultancy, where he worked with company partner Michael Bierut. Before joining Pentagram in 1990, Bierut, who had also studied at DAAP, worked for a decade with the legendary Italian designer Massimo Vignelli (1931-2014), the creator of the New York City subway map that was first issued in 1972 and a related signage system, both of which are still in use today (although the map has been revised numerous times).

Reed met Hamish Smyth, an Australian, while they were both employed at Pentagram. Smyth, who earned an undergraduate degree in design from the Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology (known as “RMIT University”) in Adelaide, had done an internship at Pentagram and was later hired full-time. Smyth also became a member of Bierut’s team, contributing to corporate-identity, publication-design, and other projects.

Reed recalled that, at Pentagram, among their clients was New York City’s Department of Transportation, for which they helped create a wayfinding system for pedestrians — freestanding panels with maps that started appearing on sidewalks in 2013. Around that time, in a basement at the company’s offices, the two designers and another colleague came across an original copy of the so-called graphics standards manual for the color-coded signage system that Vignelli and his partner Bob Noorda’s design firm Unimark had devised for New York City’s public-transportation department (now the Metropolitan Transportation Authority). It was published in 1970.

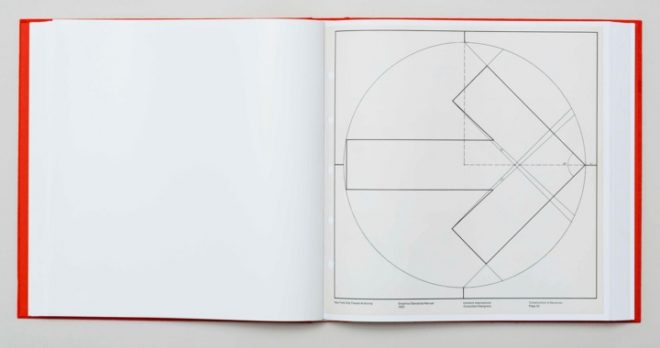

That five-ring binder, with a bright-orange cover, was filled with precise instructions about how the scheme’s plain, sans serif typeface (Standard; later Helvetica) was to be used on station-name and other informational signs, how specific colors would represent each subway line, and how directional arrows would be integrated into type-bearing signboards. For the young designers, stumbling upon the Vignelli manual was like unexpectedly discovering a lost Dead Sea scroll.

“Technically,” Reed remembered, “the book was no longer protected by copyright; its content was now in the public domain.” He and Smyth then created, as a labor of love, a website, which no longer exists, on which they posted material from that original manual. Around that time, serendipity struck again, for the city’s public-transportation agency became a Pentagram client. Meanwhile, Reed and Hamish decided to try to republish the manual in a high-quality facsimile edition. Hoping to raise just over $100,000 to cover the costs of producing one thousand copies, in 2014 they launched a Kickstarter campaign. For what it was worth, they also obtained the current MTA’s permission to republish the old Vignelli manual.

“We were stunned,” Reed told me. “We announced the fund-raising campaign online, and by noon of the first day, we had reached our goal. A big spurt of support came from other designers, for sure. Ultimately, we raised enough to be able to produce and sell roughly 8000 copies.”

That edition of New York City Transit Authority: Graphics Standard Manual instantly became a collector’s item. Printed in Italy (“No printer in the US could handle it,” Reed observed), it featured three different kinds of paper, twelve separate spot colors (rich, luscious hues produced using individual inks), a cloth cover, and a hand-sewn binding. That volume measured 13.5 inches square and featured high-resolution digital scans of each page of the original manual, in effect presenting it as some kind of preserved artifact.

“Another great coincidence,” Reed noted, “was that, when Vignelli’s son Luca, a photographer, heard about our project, he kindly loaned us his father’s personal copy of the original manual, which contained some of Massimo’s handwritten annotations. That’s the copy we used to make the scans for the reprint.”

With that ambitious project, while still working at Pentagram, Reed and Smyth established their design-book publishing company, naming it “Standards Manual.” Today, that first book is essentially out of print, with copies turning up for resale at high prices. To meet demand, though, Standards Manual issued a second, less costly, mass edition in a slightly smaller format, which is still available.

“From start to finish, that first project took us about six months,” Reed explained, adding, “We like to work fast.”

The designers went on to republish, also in meticulously crafted, facsimile form, the National Aeronautics and Space Administration’s 1975 Graphics Standards Manual, which featured an institutional-identity scheme designed by Richard Danne and Bruce Blackburn. With its orange-red, dark-gray, and black palette, and its NASA logo spelled out in a unique, geometric-serpentine typeface, Danne and Blackburn’s design program for the U.S. space agency gave it a sleek, futuristic feel. Known as the “worm,” their logo was in use until 1992, when NASA switched to a more old-fashioned symbol resembling a Boy Scout’s merit badge.

Writing in an introductory essay in the NASA Graphics Standards Manual reissue, Christopher Bonanos, the author of a history of Polaroid cameras, notes that, when Danne and Blackburn’s small, New York-based firm came up with their scheme, “Few people in those early days of NASA were thinking about graphic design. The agency was run by a mix of military folks, flyboys and bureaucrats, and not a lot of them were concerned with the field that was more often called ‘commercial art.’”

Danne had come from creating movie posters, including a memorable one for Rosemary’s Baby in 1968. Blackburn came from a background in corporate-identity design, having worked for Chermayeff & Geismar, a New York-based firm that was founded in the late 1950s and, like Vignelli Associates, occupies an important place in the history of modern communications design. Blackburn had just won a competition for the job of devising a symbol for the bicentennial celebration of the American Revolution in 1976. Of Danne and Blackburn’s design scheme for NASA, Bonanos writes, “It was bold, like NASA itself; it was technological in its swoop. The two capital As lacked crossbars, suggesting rocket nose cones or the shock waves that those nose cones produced.”

Reed and Smyth have also published a reproduction of the manual describing the use of Blackburn’s star-shaped symbol for the 1976 Bicentennial, which turned up in everything from postage stamps to license plates, as well as a reissue of the standards manual for the US Environmental Protection Agency’s graphic-design scheme, which was developed by Steff Geissbühler of Chermayeff & Geismar and published in 1977. “Graphic design for U.S. government agencies and institutions was in its infancy,” the Swiss-born Geissbühler writes in the new edition.

With these successful projects behind them, Reed and Smyth both left Pentagram earlier this year to devote their energy full-time to producing books; together, they also founded Order, a design company. Their office in the Greenpoint section of Brooklyn features a small storefront bookstore where Standards Manual’s titles and other design books are sold.

Standards Manual’s newest book, New York City Transit Authority: Objects, is not a reproduction of any earlier, graphic-design guidelines but rather something of an outgrowth of their work on the New York City subway system’s 1970 manual: hundreds of photographs of historical artifacts related to the Big Apple’s public-transportation system — old Metrocards, subway tokens, line workers’ gloves, a button commemorating the 1980 transit employees’ strike, and more — from the collection of Brian Kelley, a commercial still life photographer who began amassing Metrocards in 2011. “I have a wide range of passion projects,” Kelley told me in a recent e-mail interview, noting that his collection of maps of national parks is one of his newest.

Kelley noted that he especially appreciates the “beautiful” transit-related memorabilia he has found dating from the late 1800s through the 1970s. “After that period,” he noted, “the quality seems to go down, almost as though the people who designed the pieces stopped caring so much about what they were putting out into world.”

It’s the opposite impulse that seems to motivate Reed and Smyth as they focus on what they consider to be some of the definitive, standards-setting works of modern design, celebrating their artistic qualities while recognizing their enduring, practical contributions to the field.

That sensibility will be reflected again in Identity: Chermayeff & Geismar & Haviv, a new book they are assembling now, which will focus on the innovations of an iconic American design firm (which now bears an updated name) and will be published next spring. “It’s our first monographic book,” Reed noted, “and it marks a thematic direction we would like to explore, looking in depth at the work of certain important designers.”

In keeping with their company’s well-tested model, it is already taking customers’ advance orders for the new book. So far, they have been coming in at a steady pace, proving, perhaps, that where Standards Manual goes, devoted design nerds will enthusiastically follow.