In the 19th century, dust jackets on books were just protective paper wrappers, thrown away after a book was purchased. The prized cover was the leather underneath, and although some of these bindings had elegant designs, the dust jacket rarely referenced the interior contents. The Illustrated Dust Jacket, 1920-1970 by Martin Salisbury, out now from Thames & Hudson, chronicles how this once disposable object became a major creative force in publishing.

“In view of its origins as a plain protection to be discarded on purchase, and the relatively recent acceptance of the detachable jacket as an integral part of the book and its identity, it is ironic that for today’s book collectors the jacket is key — the presence of an original jacket on a sought-after first edition now greatly adds to its value,” Salisbury writes in the book. The Illustrated Dust Jacket concentrates on the 20th-century heyday of the dust jacket, when artists were experimenting with printing and illustration techniques, and publishers were recognizing its advertising potential. Although the first known illustrated dust jacket dates to the 1830s, this was the era in which it was actively designed.

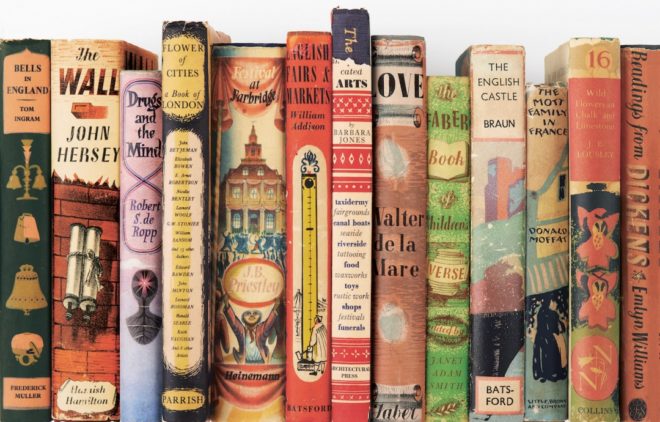

“The rapid rise of the pictorial dust jacket through the 1920s and 1930s coincided with the Art Deco period in contemporary design,” Salisbury notes. “Inevitably, the movement’s ubiquitous dynamic, geometric motifs pervaded the covers of many books.” The Illustrated Dust Jacket begins with short descriptions on the artistic movements that influenced these influential decades of book design, and then highlights over 50 of its artists through more than 300 images.

For instance, Ancona, aka Edward D’Ancona, brought a 1930s film noir aesthetic to crime fiction, while Vanessa Bell instilled a simplicity and painterly style on her sister Virginia Woolf’s books. Other early 20th-century illustrators came from the realist school, including N. C. Wyeth who studied with Howard Pyle, and involved his passion for landscapes and the natural world on covers for the 1939 The Yearling and 1928 Westward Ho!.

By the 1950s there was more of an interest in lifestyle publications that offered aspirational information on travel, food, and home improvement. Heather Standring created designs for publishers in the UK and USA, her meticulously sketched lines with punctuating color adorning the 1954 Mushroom Cooking (she later authored How to Live in Style in 1974). Alongside was a “Kitchen Sink” social realism popular in the UK, as well as the more florid, lyrical neo-romanticism.

“Many of the so-called neo-romantic artists worked across a range of fine and applied arts,” Salisbury states. “Most of the key figures illustrated books and/or contributed jacket designs, leaving us with a mini ‘golden age’ of book designs and illustration.” Hand-rendered lettering by designers like John Minton and Keith Vaughan added to the individual character of these books, enticing the reader with the promise of a transporting narrative.

Salisbury has identified numerous book illustrators, yet a large number of the dust jackets were unsigned, their creators now anonymous. And as he notes in The Illustrated Dust Jacket, even a successful designer such as Edward McKnight Kauffer, known for his use of form and geometry on covers for The Invisible Man (1952) and Intruder in the Dust (1948), was not “widely appreciated during his own lifetime in his native America.” The Illustrated Dust Jacket argues for celebrating the design and art of the dust jacket, and the often obscure creators behind these innovative covers.

The Illustrated Dust Jacket, 1920-1970 by Martin Salisbury is out now from Thames & Hudson.