For over two decades, Nicholas Bonner has taken foreigners into North Korea through the travel company he co-founded, Koryo Tours. During these many visits, he collected and saved the tickets, food labels, candy wrappers, hotel welcome cards, and other bits of ephemera he came across, finding himself enchanted by their graphic design. Selections from his personal collection are now published by Phaidon in Made in North Korea, a beautifully designed book that highlights the relationship between the country’s visual culture and its national identity.

The collection represents a subjective, personal archive rather than a thorough survey of North Korean’s design ephemera. Eight short essays by Bonner on topics such as brand identity, the production of graphics, and ephemera for tourists add a personal touch to the tome; even more stories are told through captions that shed light on daily life in the isolated country.

Because all product packaging is designed for state approval, the visuals present a clearly recognizable “house style,” as Bonner puts it, which has largely remained consistent particularly because designers receive little exposure to foreign influence. Designs are typically very simple: unlike Western ads, they are crafted to inform rather than seduce. Nonetheless, they are aesthetically pleasing and cleverly executed, incorporating images that celebrate North Korean culture.

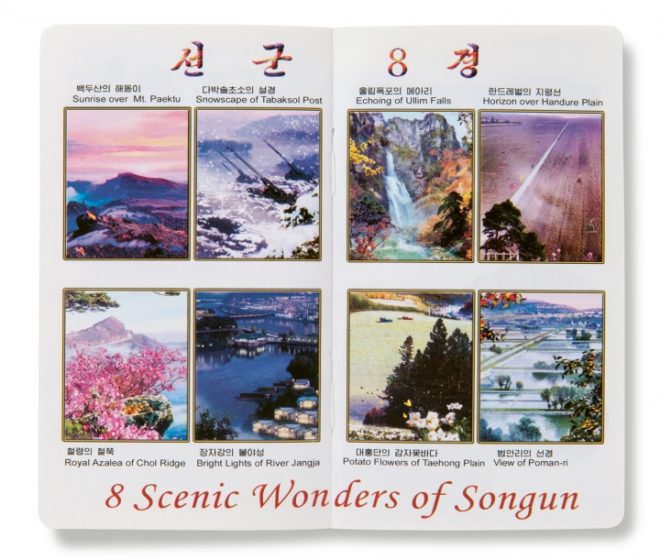

Many of the objects Bonner has collected feature traditional motifs such as the national flower — the magnolia — or cranes and pine trees, which are symbols of longevity and health. The Workers’ Party emblem also often appears on everyday objects like greeting cards, envelopes, and event tickets. Well-known North Korean landmarks, too, are popular pictorial tropes intended to stir national pride: an image of Mount Kumgang represents Korean strength and citizens’ good health; depictions of a steel plant nods to the country’s powerful industrial forces. Placing these images on everyday items imbues them with what Bonner describes as a “instantly recognizable Koreanness” that marks a product as the best possible option available.

“North Koreans are taught, starting in kindergarten, to value their country and society in non-material terms,” Bonner writes in one essay. “There is absolute common understanding that their country is ‘the best’ not because it has the most money or material goods, but because it is ‘Korean … The idea that North Korea is best is reinforced and amplified in the graphic identity of all manner of products.’”

Most of the objects in Made in North Korea are from trips Bonner made between 1993 to 2005, from the bars he visited to hotels that sheltered him to the Air Koryo flights he took to and fro Beijing. The more recent objects reveal how packaging was gradually shifting, particularly after July 2002, when North Korea introduced major economic reforms that allowed private markets to emerge. While, for decades, designs were mostly hand-drawn, products with digitally rendered packaging began to dominate shelves to compete with the growing influx of international brands. And as North Korean artists received more outside influences, their designs evolved into a more globalized style, becoming more polished but more also more uniform.

As Bonner describes it, the period on which his book centers is a “golden age” of graphic design in the DPRK, when commercial designs focused on craftsmanship above competition and spoke directly to a specific culture.

Made in North Korea is available through Phaidon.